Despite 400 years of contact with Europe, most African kingdoms and chiefdoms—even those on the coast—had no idea what the European nations were up to in the late 19th century. Africans had no idea that Europeans had shared African territory among themselves at a conference in Berlin and were planning to take over the continent.

While major newspapers in the capitals of Europe rushed news of the conference to readers every morning, Africans had no such information dissemination mechanisms, and were completely in the dark about what was going on. In the words of the late Professor Adu Boahen, eminent African historian of colonialism, the most surprising thing about the imposition of colonialism was “its suddenness and unpredictability.”

Yes, it was sudden and unpredictable to the Africans. But it should not have been. Europeans had been nibbling away at the coast of Africa for decades and had declared some places such as Lagos “Protectorates”. And we know they engaged that coastal kingdom not with flowers and kisses, but with blood and iron. Nevertheless many African leaders were not immediately worried. Some like Al Hajj Umar, who led a 19th century jihad in the Senegambia, completely misunderstood the Europeans. “The whites are only traders,” he is reported to have said.

In 1884, these “traders” led by Otto von Bismarck, the “Iron Chancellor” of Germany, held a conference in Berlin where representatives of the major European powers, and the United States (which was a mere onlooker) decided who would control what part of Africa. He invited all the major world players like Britain, France, Russia, and Austro-Hungary, and, of course, no Africans were asked to attend.

Bismarck, who had a few decades earlier created a new European military and industrial power from Prussia and some German speaking independent states, was initially not interested in colonies in Africa. But he soon changed his mind, and declared German “Protectorates” in Togoland, Cameroons, German East Africa, and South West Africa. The “Scramble for Africa” was on, and this led to the conference, where the Europeans sought to divide up the continent peacefully—for the European countries of course, not the Africans.

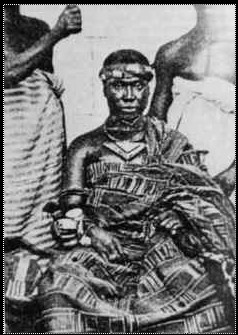

It wasn’t long before some of the African kings and high chiefs found out that the Europeans sought to deny them their sovereignty. Prempeh I, emperor of Ashanti, was offered “Protection” by the British in 1891. He told them that “my kingdom would never commit itself to such a policy.” Similarly, King Wobogo of the Mossi told French Captain Destenave who had come on a similar mission: “I know the whites wish to kill me in order to take my country, and yet you claim that they will help me to organize my country… I have no need [for your help]…consider yourself fortunate that I do not order your head to be cut off. Go away now, and above all, never come back.” Such fighting words were expressed by many African leaders, words they unfortunately could not back up with deeds.

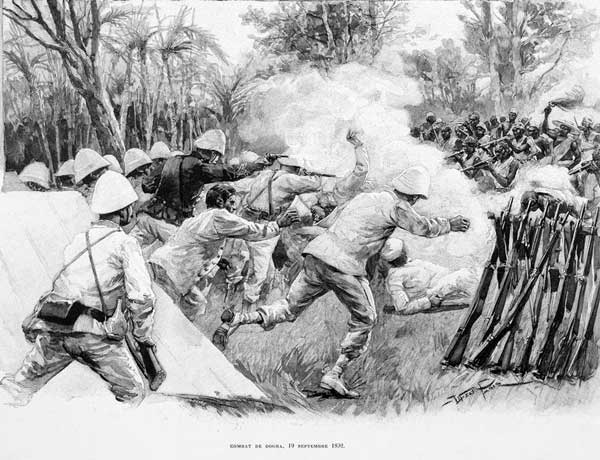

So what did they do to prepare for the inevitable invasion? Many resorted to juju and religion. Wobogo, for instance, sacrificed a black cock, a black ram, a black donkey and a black slave to the earth goddess, appealing to her to crush the French. Well, the earth goddess was helpless before modern French arms.

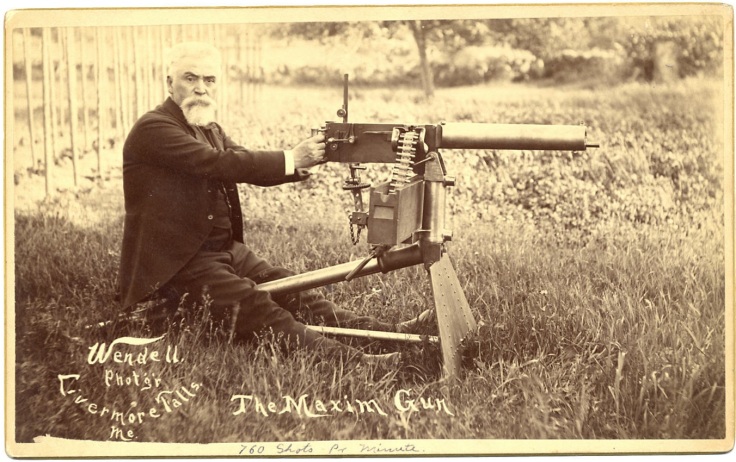

European arms had undergone significant change in the prior decades. The mid-to-late 19th century was a time of the mass introduction of rifled, (grooves made in the barrel that made the projectile spin and therefore travel more accurately) breech-loading guns of all sizes, explosive shells rather than solid shot cannon balls, repeater rifles, and the early machine gun. These destructive weapons were revolutionary, and they transformed warfare, and were responsible for the unexpected mass slaughter of World War I (1914-1918). It is important to note that the Berlin Conference forbade the sale of these new weapons to Africans.

Other African leaders took measures that were slightly better than Wobogo’s actions, but no less ineffectual. Prempeh of Ashanti and Lobengula of the Ndebele sent diplomatic delegations to see Queen Victoria, hoping to head off the invasion by appealing to the constitutional monarch of England. They had heard so much about her from British emissaries and heard from the emissaries how they were acting in her good name, that they were sure she was the benevolent leader who would listen to their heartfelt appeals, and stop the nonsense. Of course these delegations were ignored by the real British decision makers, the parliament and ministers.

Most African leaders simply did nothing. They thought they could handle the Europeans militarily as easily as they had in previous centuries. They had no idea things had changed in fundamental ways. As Adu Boahen writes, “As far as Africans were concerned…they were confident that if the Europeans wanted to force any changes on them and push their way inland, they would be able to stop them as they had been able to do for the last two or three hundred years. Hence the note of confidence, if not defiance, that rings through the[ir] words….”

Their biggest failure was their lack of modernization despite centuries of contact with Europe. They did not understand any of the changes that were going on in Europe, changes that would propel Europe so far ahead that Africans would not be able to catch up in the time available.

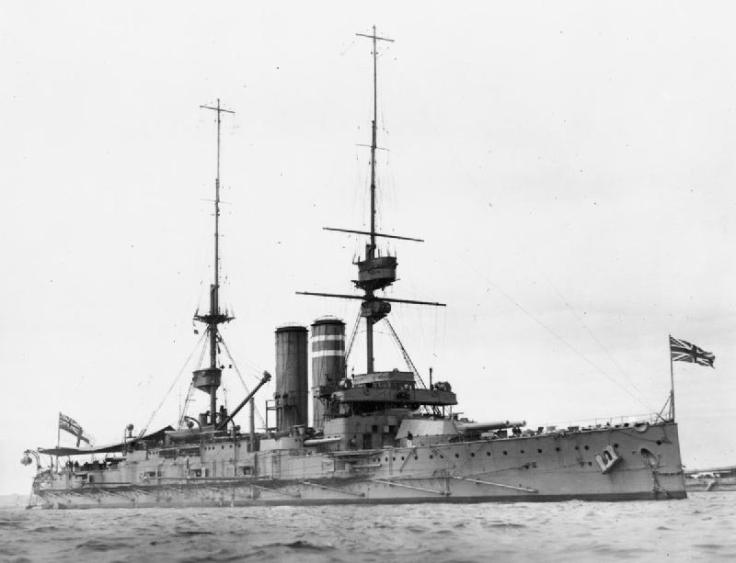

The transformations in Europe went well beyond the technological innovations in weaponry. For example, in England, there were various organizational and bureaucratic changes that began as far back as the 16th century under Henry VIII. This involved building and constructing a standing navy that incorporated the latest innovations, and an equally important standing naval administration to support and manage it. This gave Britain the ability to project its power far beyond its shores. Capable officials and managers were appointed to run things. Raising and running the navy was no longer one of the King’s jobs, in the way it remained so in many monarchies where a usually incompetent and untrained person pulled all the strings as best as he could. In Africa, things were even worse, and temporary armies were raised for war from age grades in a very disorganized and ad hoc fashion.

It is very difficult to blame Europe for behaving like human predators in the presence of prey, when Africans did everything they could to present themselves as prey available to be eaten. Humans are predators, an unfortunate fact of existence. Humans consume other animals as well as consume their own figuratively if not literally. All human communities have to do whatever they can to prepare for and resist predatory acts by foreign actors.

Africans failed in the area that British historian and professor of Classics at Stanford Ian Morris calls “social development.” To quote him, “Social development is the bundle of technological, subsistence, organizational, and cultural accomplishments through which people feed, clothe, house, and reproduce themselves, explain the world around them, resolve disputes within their communities, extend their power at the expense of other communities, and defend themselves against others’ attempts to extend power. [my emphasis] Social development, we might say, measures a community’s ability to get things done….” (p 144, Why the West Rules For Now)

In my next post, we will look at what some other non-African parts of the world did in response to Western encroachment.

SOURCES

UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol VII: Africa under colonial domination 1880-1935, editor A. Adu Boahen.

The Cambridge History of Africa Vol 6, from 1870 to 1905, editors, J.D. Fage and Roland Oliver

The Scramble for Africa by Thomas Pakenham

Africa Since 1800 by Roland Oliver and Anthony Atmore

African Perspectives on Colonialism by A. Adu Boahen

Why the West Rules for Now: the patterns of history and what they reveal about the future, by Ian Morris.

War Made New: Weapons, warriors, and the making of the modern world, by Max Boot.

Africa and The West: A documentary history, vol 1: from the slave trade to conquest, 1441-1905, editors, William Worger, Nancy Clark, Edward Alpers

Interesting view. I don’t blame them in that era as much as I do our leaders now. In the abundance of knowledge and experience, we and our so-called leaders, continue to mess up.

LikeLike

Thanks Sami for your response. I agree with you that we Africans today should be in a position to do better.

LikeLike

Our leaders and Europeans both were at fault. The mass deportation of so many people allowed for creativity to dead end itself. Imperial wars fought in Africa had a unit of Afro Caribbeans, whose ancestors were ironically sent from said area.

LikeLike